London Guide Series: Grime as a Gateway

Grime as a gateway into the heart and soul of London.

The London Guide is an unconventional city guide for people who travel for culture, rather than traditional tourist attractions and viral food spots. The series looks at creative genres birthed in London, with the premise that the conditions and influences that led to its creation, the stories of the artists and the topics they talk about, tell you more about a city than a traditional guidebook. The first part of this series is on Grime.

“We’ve been ahead for so long in the UK, we’re so multicultural and that’s the beauty,” he says. “That’s why grime was formed, from this mix, this understanding of different people. Now other people are catching on. There’s a revolution happening.” Skepta in The Guardian

From the outside, if someone unfamiliar with the culture were to look in, they probably wouldn’t see the beauty in grime. They might see it as noise. A young thing. A Black thing. Something not to be considered seriously or respected as art.

They wouldn’t see that a group of kids from East London’s estates managed to create an entirely homegrown sound that distinctively captured the essence of London.

They wouldn’t see the talent, creativity and determination of the early-day artists whose DIY attitude saw them selling CDs in the street, hosting illegal raves, broadcasting on pirate radio, making their own music videos and creating their own merch.

They wouldn’t feel the awe that this artform, born out of working-class communities in areas mostly associated with poverty and crime, has gone on to create a wider culture that has influenced and inspired a generation of Black British and working-class creatives.

Dizzee Rascal, Boy in da Corner (2003), a breakout album

For those who are unfamiliar, grime is a “genre of electronic music that…evolved out of UK garage and is influenced by drum and bass, dancehall, ragga, and hip hop. Grime music is generally produced around 137-143 beats per minute, with its aggressive, jagged electronic sound.” Truth be told, a Wiki definition can’t fully convey what it is. You have to feel it for yourself. It’s grit and anger and passion and energy. It’s the sound of London.

In ‘The Creative Act,’ Rick Rubin describes art as being “the reflection of the artist’s inner and outer world during the period of creation.” So if we look at grime’s creation, we find a generation of young boys coming of age in a time when jungle and garage - other UK genres - dominated the local music scene. But the flashiness of garage didn’t reflect what they were feeling or how they wanted to express themselves. “A bit of a separation happened between the garage crew who were still going for their female vocal tracks, all very fluffy and two-step. We wanted to make music for these MCs to say lyrics about our local area and our lives. That’s where grime was born.” DJ Target for Another Man. The music evolved into something darker and grittier. Until then, the U.S. heavily influenced UK rap, but this new generation kept it local, keeping their strong London accents and infusing their lyrics with British slang, while still taking inspiration from the Jamaican MCs that had influenced garage music.

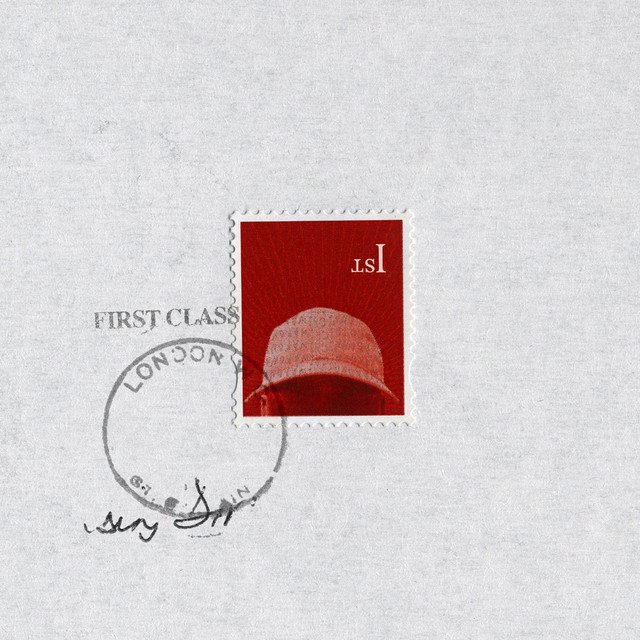

Skepta, Konnichiwa (2016), credited with grime's resurgence

What’s special about grime and other Black British music genres is that if you trace their roots, you’re presented with a morphing of sounds birthed from the soundsystem culture that developed in the UK following the arrival of Windrush (the generation from the Caribbean who travelled to fill post-war labour shortages in Britain from 1948). You can see how the sound has evolved throughout the years to reflect the time and generation, with each genre showing a part of history and the story of the city. This journey reflects the purpose of this series - to use creativity as a gateway into the Black British culture that isn’t included in traditional tourist media. It’s for grime to act as a prompt for deeper exploration and connection with the city beyond Buckingham Palace, Shakespeare’s Globe, and Harry Potter. It might lead you to a music show or it might lead you a traditional East End caff or a beloved Caribbean takeaway spot. It might lead you to musicians beyond the grime scene itself, to other genres, art forms or manifestations of Black British culture.

While grime has evolved, its influence is still evident in the rap coming out of the UK today. Many of its original stars have supported emerging talent and transitioned into other creative careers (spot Kano in Top Boy and The Kitchen, and Ghetts in Supacell, while Skepta is moving between DJing, art and fashion). Their influence extends beyond music, leaving a lasting impact on the British creative landscape

“Grime cannot die at this point—its culture lives on in everything from drill to Top Boy.” Complex

Here’s a selection of songs, podcasts, books, articles and videos to get you started.

Listen:

Dizzee Rascal - I Luv U - one of the first grime songs to gain mainstream attention in 2003

Kano - P’s and Q’s - a classic released in 2005 by one of the UK’s best rappers. Don’t miss his albums Made in the Manor and Hoodies All Summer

JME - Man Don’t Care - a grime anthem that you need to experience in a crowd. Angry lyrics with references to Harry Potter, tea and digestive biscuits - what’s not to love?

Skepta and JME - That’s Not Me - described by Vice as ‘grime’s redemption song,’ Skepta’s ‘Konnichiwa’ album is often credited as helping grime shift from underground to mainstream in 2016

Podcast: Sounds of Black Britain - Rise of Jungle, Garage, and Grime

Read:

Grime Transformed British Music. A New Exhibition Traces How

Skepta’s Konnichiwa changed UK music forever, we should celebrate it as much as The Beatles or Oasis

Watch:

Chicken Shop Date (originally started with the host interviewing grime artists)

Visit:

Cafe East - “A reputation for respecting Bow's music history”

Bluejay Cafe - Stormzy’s favourite cafe

Cook Daily - “Vegan Star of the U.K. Grime Scene”

Jumbi - bar and restaurant celebrating the sounds & flavours of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora